America’s Gilded Youth Go Berserk, Sometimes

Why the meritocracy’s children are choosing murder over management consulting.

There's something darkly comic about an Ivy League educated scion of Baltimore real estate royalty being caught at McDonald's, that golden-arched cathedral of late capitalism, hash browns in hand, allegedly fresh from assassinating a healthcare CEO. McDonald's, whose Moscow opening in 1990 had Soviet citizens lining up for hours, convinced that a Quarter Pounder with Cheese would deliver them into the promised land of Western abundance.

Luigi Mangione, valedictorian turned vengeful revolutionary, ordered his last capitalist meal before the cops caught up with him. The Monopoly money reportedly found in his backpack reads like a heavy-handed metaphor that even Don DeLillo would reject as too on-the-nose.

I was reminded of my fave author Phillip Roth, who once said that American life was becoming so surreal, so stupefying, that it had ceased to be a manageable subject for novelists. It’s not just that the headlines are stranger than fiction, it’s that actual American life had become so thoroughly deranged, so perfectly engineered for maximum psychic damage, that attempting to novelize it was like trying to satirize a circus clown having a mental breakdown at a children's bday party.

The half-tragedy, half-farce that is the Luigi Mangione story, is a familiar motif in fiction and in real life: the privileged child who turns against the machine that manufactured them.

In his Pulitzer-prize winning novel, American Pastoral, Philip Roth gave us Merry Levov, the stuttering affluent teenager from suburban New Jersey who bombs her local post office. Osama bin Laden traded his billions and a life of Saudi wealth and affluence for a cave in Tora Bora. And today, Luigi, who apparently decided that the best use of his Penn degrees was to wage one-man warfare against the insurance industry.

The question isn't why these gilded youth occasionally go berserk - it's why they don't do it more often. Modern American life is a masterclass in alienation: endless Zoom calls where we pretend to care about quarterly projections while secretly doomscrolling, dating apps that turn romance into a dystopian product catalog, $7 lattes that promise community but deliver only the performative friction of standing in line with strangers. We're all playing at connection while drowning in isolation, mainlining social media dopamine hits just to feel something approximating human contact. When you've been groomed since birth to excel at this game of hollow achievements and digital gold stars, maybe shooting the referee starts to make its own kind of sense.

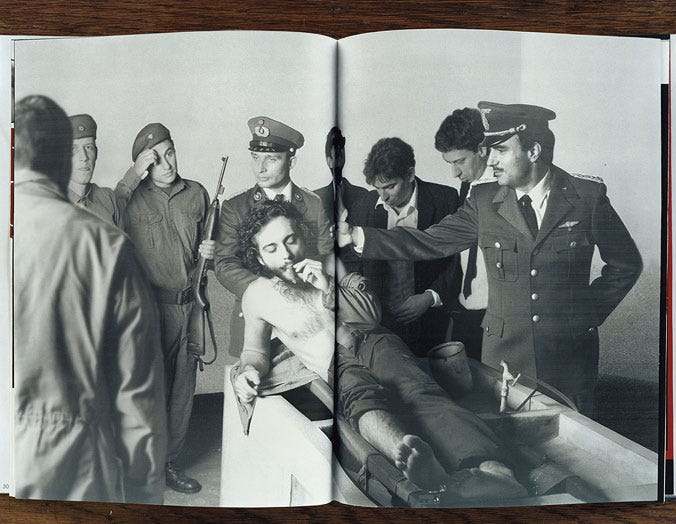

It's no accident that our disaffected elites still cling to the myth of Che Guevara, that perfectly branded revolutionary whose face adorns dorm room posters and overpriced made-in-China t-shirts. Not even the mass exodus of Cuban raft people or Castro's descent into isolated paranoia has dimmed Che's appeal as the patron saint of privileged rebellion. He offers what every alienated Ivy League revolutionary craves: the hope for a better world, packaged in an aesthetically pleasing narrative of sacrifice for the downtrodden. It's Christianity for people who think they're too smart for religion, complete with its own photogenic Christ figure. The myth of Luigi is the myth of a privileged life sacrificed on the altar of the disinherited, the