When Jesus Took the Wheel

How Christianity took over the Roman Empire

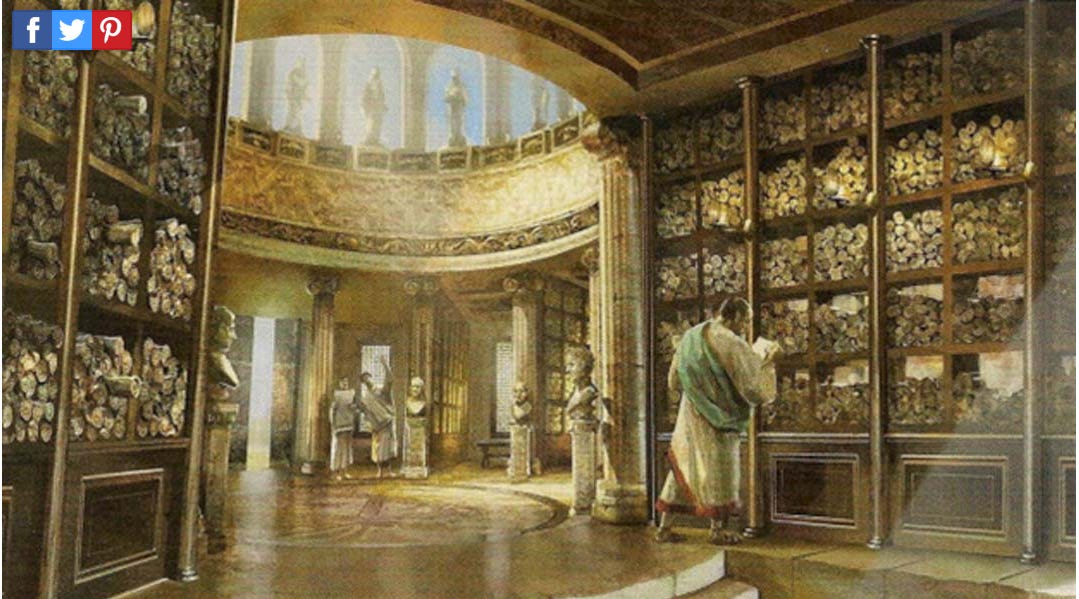

Alexandria, 391 CE. A mob of Christ-pilled zealots, led by Theophilus, a bishop with the unhinged energy of a 4Chan moderator, storms the Serapeum, a sprawling mega temple of a Greco-Egyptian composite god named Serapis who was the patron god of the city. This wasn’t just a temple; it was also the last gasp of the Library of Alexandria, housing the world’s knowledge after the main library got torched in earlier imperial fumbles.

The Library of Alexandria was essentially the ancient world’s Internet, a repository of all human knowledge, complete with its own search engine of catalogers and citation system. The mob of Christians were now swinging their big deity energy, smashing statues and burning the library. It was like if someone today managed to simultaneously erase Wikipedia, the Library of Congress, and everyone’s hard drives.

This culturally genocidal moment is why historians mark 391 CE as classical antiquity’s technical time of death. The destruction of the Serapeum wasn’t just Christian fundamentalists throwing a tantrum - it was the definitive announcement that the classical world had been euthanized and Late Antiquity was about to go medieval. The Roman Empire was trading marble columns for martyr vibes and ushering in the Middle Ages.

So how did Christianity take over Rome? How did a tiny cult metamorphose from imperial chum to Rome’s masters in just three centuries?

We know, of course, that Christianity started as Rabbinical Judaism’s messianic cousin. It wasn’t the only cousin. There were many messianic movements that sprang in the aftermath of the Roman destruction of the second temple in Jerusalem in 70 CE. There was Simon bar Giora, John of Gischala, Theudas and of course Bar Kokhba. All of those messianic movements had something that set them apart from world religions at the time: their apocalyptic worldview.

Jewish texts like Daniel, Isaiah, Enoch, and Zechariah all forecasted divine judgment and end-time deliverance. The idea of a coming Messiah and a purified world order was already baked into scripture, and was particularly attractive in ancient Judea which was reeling under Roman occupation. Essentially, it was a belief that a final cataclysm would violently overturn the current world order. God would vindicate the righteous, punish the wicked, and restore Israel.

This was unique in that no other people, whether Romans or peoples conquered by Romans (the Gauls, the Phoenicians, the Greeks, the Persians, the Egyptians, the Goths, etc.), had the theological expectation that their national suffering must culminate in an eschatological showdown.