Why Does Your Brain Want to Throw Tesla's Robot Down a Well?

On ogres, hobbits, trolls, and the ancient lore of Neanderthals getting yeeted from the gene pool.

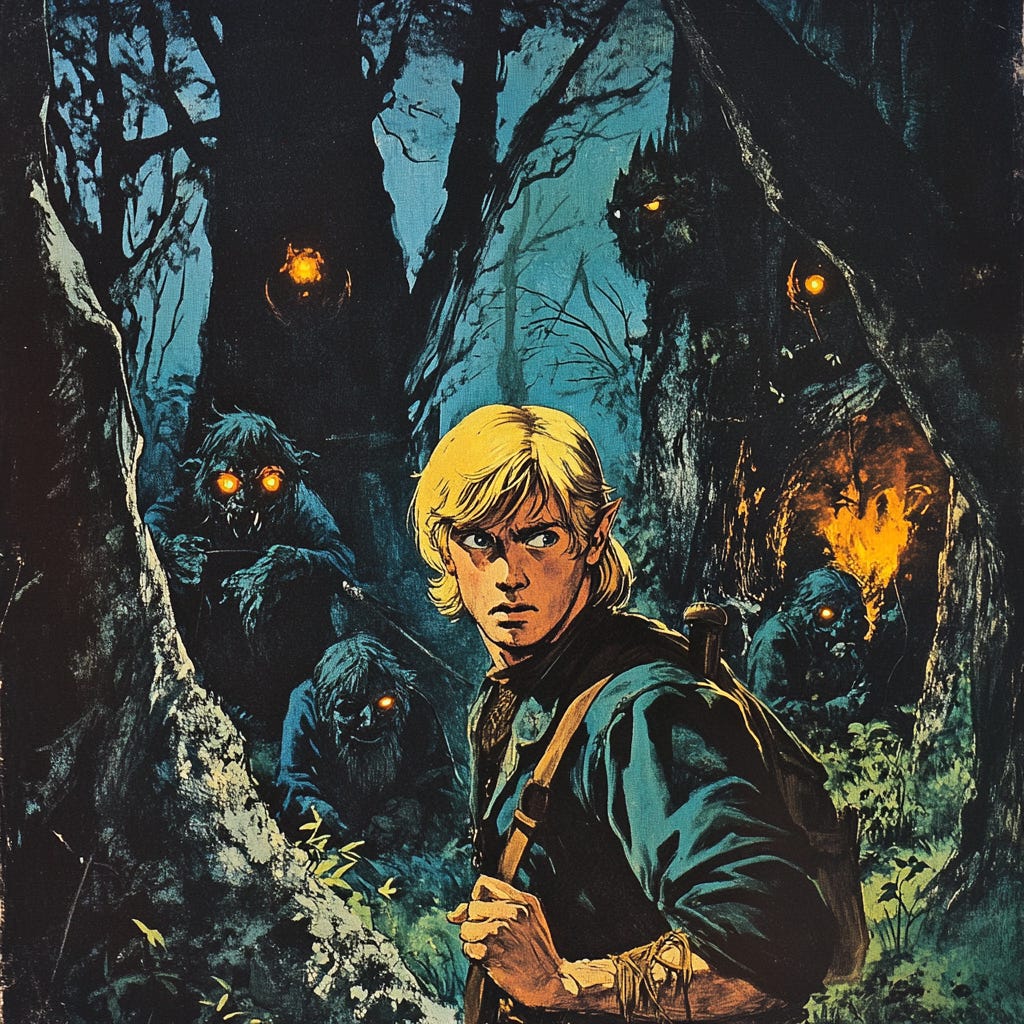

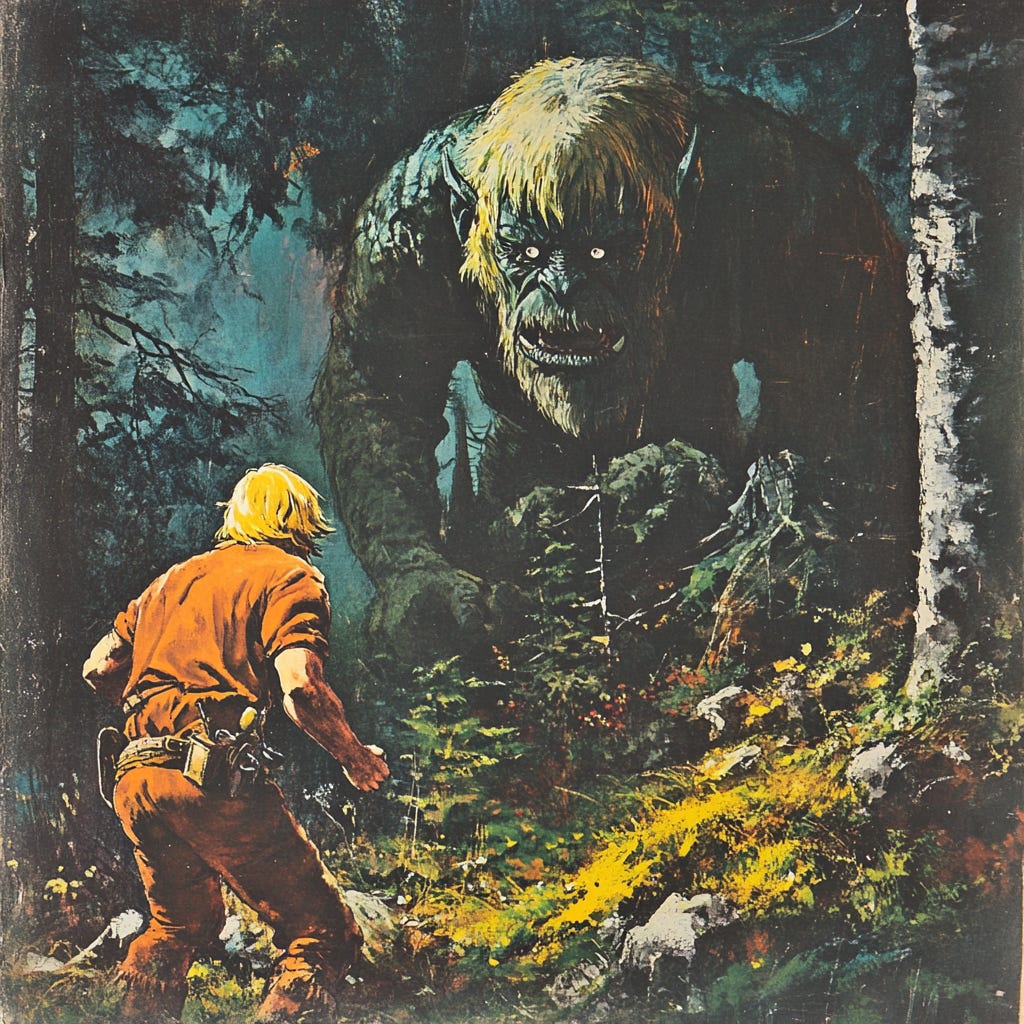

It’s a crisp autumn night in medieval Scandinavia. A woodcutter returns home through the ancient forest, axe slung over his shoulder, when a flicker of movement stops him cold. The old stories whisper in his ears—warnings passed down through generations about the jötnar, of Norse mythology, that dwell in these woods. As moonlight filters through bare branches, he glimpses the creature: powerful build, slightly stooped posture, heavy brow shadowing deep-set eyes. Not quite an animal, yet somehow wrong for a human. Its movements are deliberate but strange, as though operating under slightly different physical laws. Most unsettling is its face—almost readable but with expressions that don't quite land. Primordial terror overcomes the woodcutter, not the clean fear of a wolf or bear, but something more insidious—the dread of encountering something that occupies the uncanny borderlands of humanity itself. He will later describe the creature to wide-eyed villagers as a "troll"—strong enough to uproot trees, cunning enough to work stone and hide, with a sloping forehead and powerful hands. His description will be dutifully added to the collective folklore, recorded with the precision of observers who understand that specificity might save lives.

Have you ever felt a strange, skin-crawling sensation when looking at something that's almost human... but not quite?

For most of human history, we maintained a relationship with our creations that was about as intellectually nuanced as a toddler's attachment to their security blanket. The more something resembled us, the harder our dopamine receptors fired, like narcissists catching glimpses of themselves in every reflective surface.

This is why we give cartoon characters those grotesquely oversized eyes (the aesthetic equivalent of evolutionary clickbait), why we project personalities onto pets that literally eat their own poop, and why middle-aged men name their mid-life-crisis convertibles and talk to them while washing them.

This embarrassingly predictable correlation made perfect evolutionary sense, of course. If something looked human, it probably was human, which meant it could either help you not get eaten by a sabertooth tiger or contribute genetic material to your attempt to replicate your DNA. Our brains developed an instinctive positive response to human features.

And yet, something strange is happening: we are witnessing a primitive psychological response that reveals something about the darkest and most enduring myths in human history. That perhaps they weren’t myths at all.

Last year, in a sterile laboratory in Tokyo, scientists were